Electrification

How Clean is the Nickel and Lithium in a Battery?

The following content is sponsored by Wood Mackenzie

How Clean is the Nickel and Lithium in a Battery?

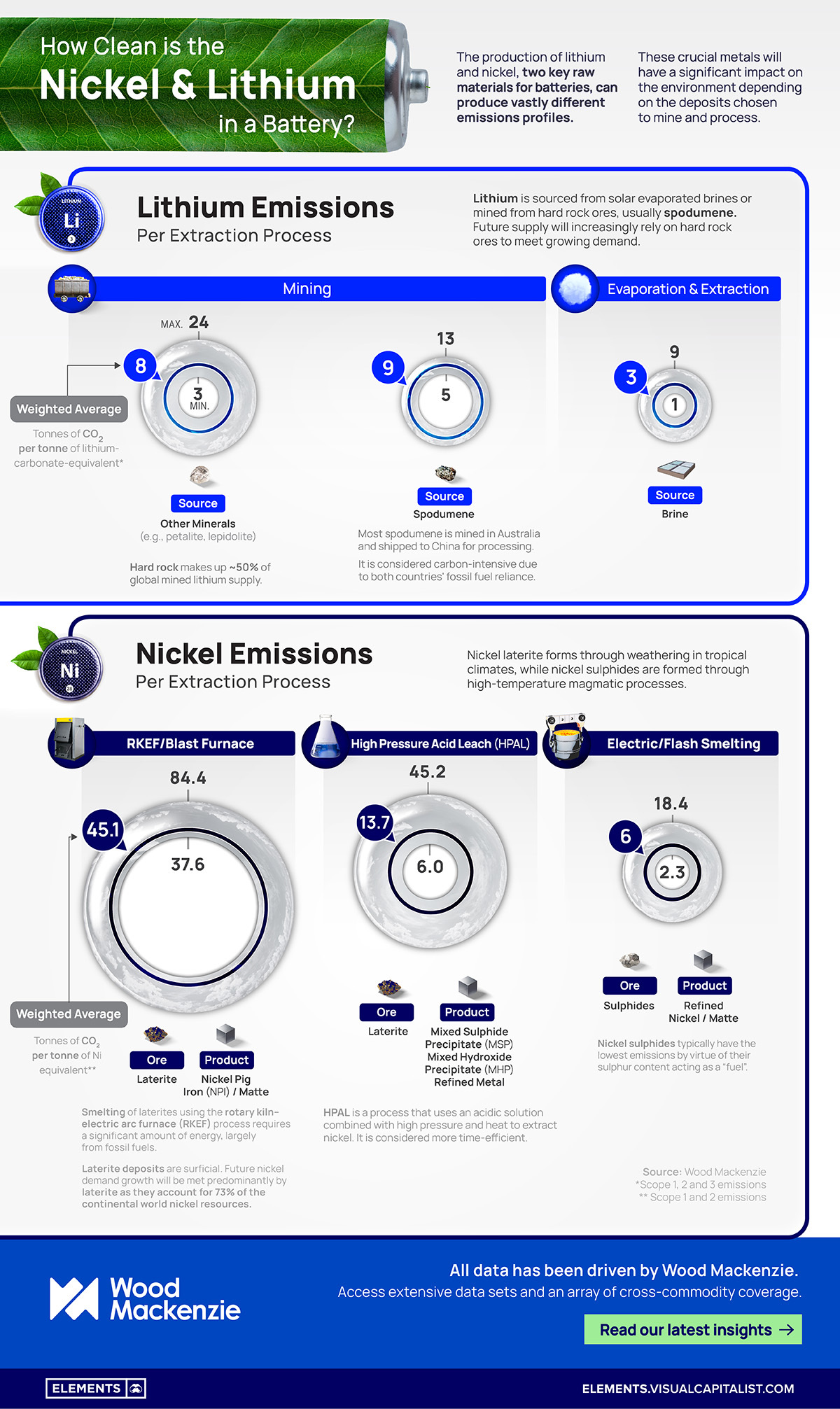

The production of lithium (Li) and nickel (Ni), two key raw materials for batteries, can produce vastly different emissions profiles.

This graphic from Wood Mackenzie shows how nickel and lithium mining can significantly impact the environment, depending on the processes used for extraction.

Nickel Emissions Per Extraction Process

Nickel is a crucial metal in modern infrastructure and technology, with major uses in stainless steel and alloys. Nickel’s electrical conductivity also makes it ideal for facilitating current flow within battery cells.

Today, there are two major methods of nickel mining:

-

From laterite deposits, which are predominantly found in tropical regions. This involves open-pit mining, where large amounts of soil and overburden need to be removed to access the nickel-rich ore.

-

From sulphide ores, which involves underground or open-pit mining of ore deposits containing nickel sulphide minerals.

Although nickel laterites make up 70% of the world’s nickel reserves, magmatic sulphide deposits produced 60% of the world’s nickel over the last 60 years.

Compared to laterite extraction, sulphide mining typically emits fewer tonnes of CO2 per tonne of nickel equivalent as it involves less soil disturbance and has a smaller physical footprint:

| Ore Type | Process | Product | Tonnes of CO2 per tonne of Ni equivalent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sulphides | Electric / Flash Smelting | Refined Ni / Matte | 6 |

| Laterite | High Pressure Acid Leach (HPAL) | Refined Ni / Mixed Sulpide Precipitate / Mixed Hydroxide Precipitate | 13.7 |

| Laterite | Blast Furnace / RKEF | Nickel Pig Iron / Matte | 45.1 |

Nickel extraction from laterites can impose significant environmental impacts, such as deforestation, habitat destruction, and soil erosion.

Additionally, laterite ores often contain high levels of moisture, requiring energy-intensive drying processes to prepare them for further extraction. After extraction, the smelting of laterites requires a significant amount of energy, which is largely sourced from fossil fuels.

Although sulphide mining is cleaner, it poses other environmental challenges. The extraction and processing of sulphide ores can release sulphur compounds and heavy metals into the environment, potentially leading to acid mine drainage and contamination of water sources if not managed properly.

In addition, nickel sulphides are typically more expensive to mine due to their hard rock nature.

Lithium Emissions Per Extraction Process

Lithium is the major ingredient in rechargeable batteries found in phones, hybrid cars, electric bikes, and grid-scale storage systems.

Today, there are two major methods of lithium extraction:

-

From brine, pumping lithium-rich brine from underground aquifers into evaporation ponds, where solar energy evaporates the water and concentrates the lithium content. The concentrated brine is then further processed to extract lithium carbonate or hydroxide.

-

Hard rock mining, or extracting lithium from mineral ores (primarily spodumene) found in pegmatite deposits. Australia, the world’s leading producer of lithium (46.9%), extracts lithium directly from hard rock.

Brine extraction is typically employed in countries with salt flats, such as Chile, Argentina, and China. It is generally considered a lower-cost method, but it can have environmental impacts such as water usage, potential contamination of local water sources, and alteration of ecosystems.

The process, however, emits fewer tonnes of CO2 per tonne of lithium-carbonate-equivalent (LCE) than mining:

| Source | Ore Type | Process | Tonnes of CO2 per tonne of LCE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mineral | Spodumene | Mine | 9 |

| Mineral | Petalite, lepidolite and others | Mine | 8 |

| Brine | N/A | Extraction/Evaporation | 3 |

Mining involves drilling, blasting, and crushing the ore, followed by flotation to separate lithium-bearing minerals from other minerals. This type of extraction can have environmental impacts such as land disturbance, energy consumption, and the generation of waste rock and tailings.

Sustainable Production of Lithium and Nickel

Environmentally responsible practices in the extraction and processing of nickel and lithium are essential to ensure the sustainability of the battery supply chain.

This includes implementing stringent environmental regulations, promoting energy efficiency, reducing water consumption, and exploring cleaner technologies. Continued research and development efforts focused on improving extraction methods and minimizing environmental impacts are crucial.

Sign up to Wood Mackenzie’s Inside Track to learn more about the impact of an accelerated energy transition on mining and metals.

Electrification

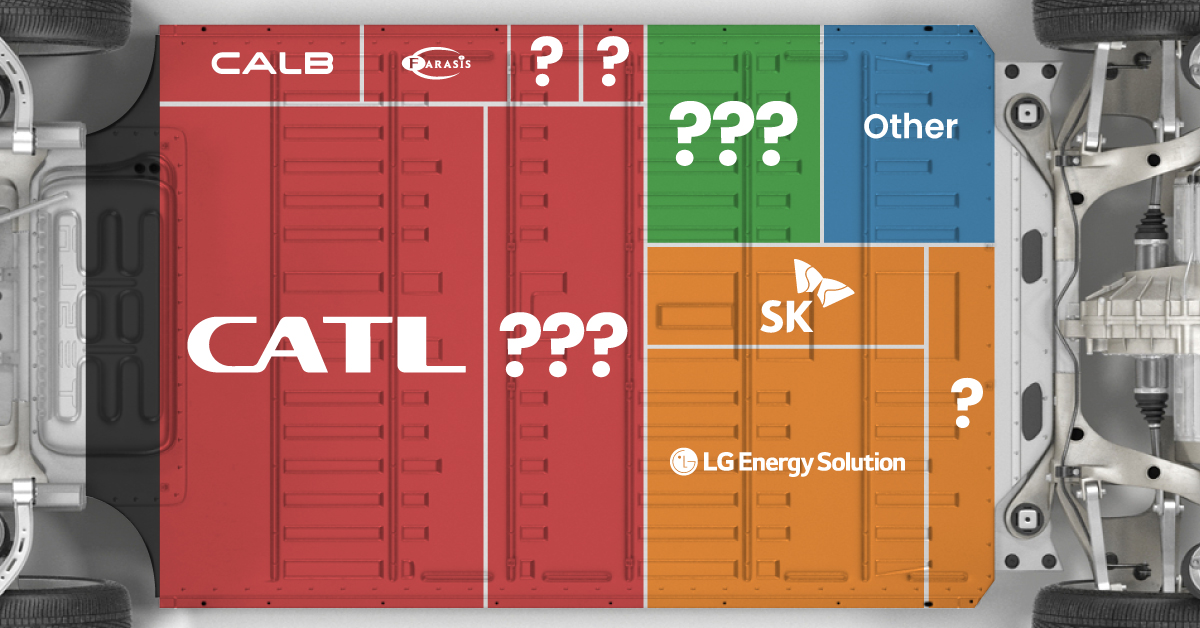

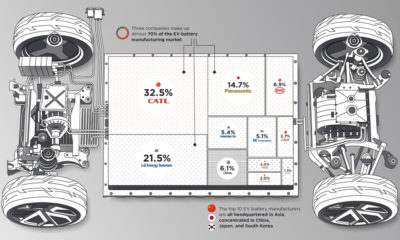

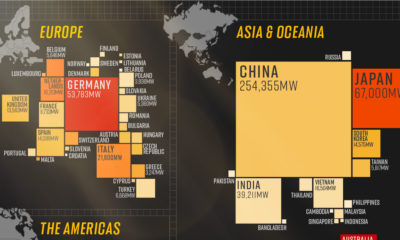

Ranked: The Top 10 EV Battery Manufacturers in 2023

Asia dominates this ranking of the world’s largest EV battery manufacturers in 2023.

The Top 10 EV Battery Manufacturers in 2023

This was originally posted on our Voronoi app. Download the app for free on iOS or Android and discover incredible data-driven charts from a variety of trusted sources.

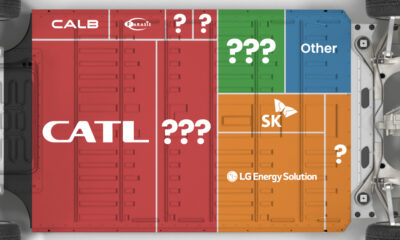

Despite efforts from the U.S. and EU to secure local domestic supply, all major EV battery manufacturers remain based in Asia.

In this graphic we rank the top 10 EV battery manufacturers by total battery deployment (measured in megawatt-hours) in 2023. The data is from EV Volumes.

Chinese Dominance

Contemporary Amperex Technology Co. Limited (CATL) has swiftly risen in less than a decade to claim the title of the largest global battery group.

The Chinese company now has a 34% share of the market and supplies batteries to a range of made-in-China vehicles, including the Tesla Model Y, SAIC’s MG4/Mulan, and Li Auto models.

| Company | Country | 2023 Production (megawatt-hour) | Share of Total Production |

|---|---|---|---|

| CATL | 🇨🇳China | 242,700 | 34% |

| BYD | 🇨🇳China | 115,917 | 16% |

| LG Energy Solution | 🇰🇷Korea | 108,487 | 15% |

| Panasonic | 🇯🇵Japan | 56,560 | 8% |

| SK On | 🇰🇷Korea | 40,711 | 6% |

| Samsung SDI | 🇰🇷Korea | 35,703 | 5% |

| CALB | 🇨🇳China | 23,493 | 3% |

| Farasis Energy | 🇨🇳China | 16,527 | 2% |

| Envision AESC | 🇨🇳China | 8,342 | 1% |

| Sunwoda | 🇨🇳China | 6,979 | 1% |

| Other | - | 56,040 | 8% |

In 2023, BYD surpassed LG Energy Solution to claim second place. This was driven by demand from its own models and growth in third-party deals, including providing batteries for the made-in-Germany Tesla Model Y, Toyota bZ3, Changan UNI-V, Venucia V-Online, as well as several Haval and FAW models.

The top three battery makers (CATL, BYD, LG) collectively account for two-thirds (66%) of total battery deployment.

Once a leader in the EV battery business, Panasonic now holds the fourth position with an 8% market share, down from 9% last year. With its main client, Tesla, now effectively sourcing batteries from multiple suppliers, the Japanese battery maker seems to be losing its competitive edge in the industry.

Overall, the global EV battery market size is projected to grow from $49 billion in 2022 to $98 billion by 2029, according to Fortune Business Insights.

Electrification

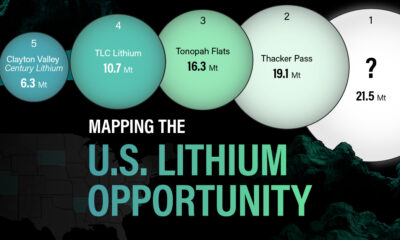

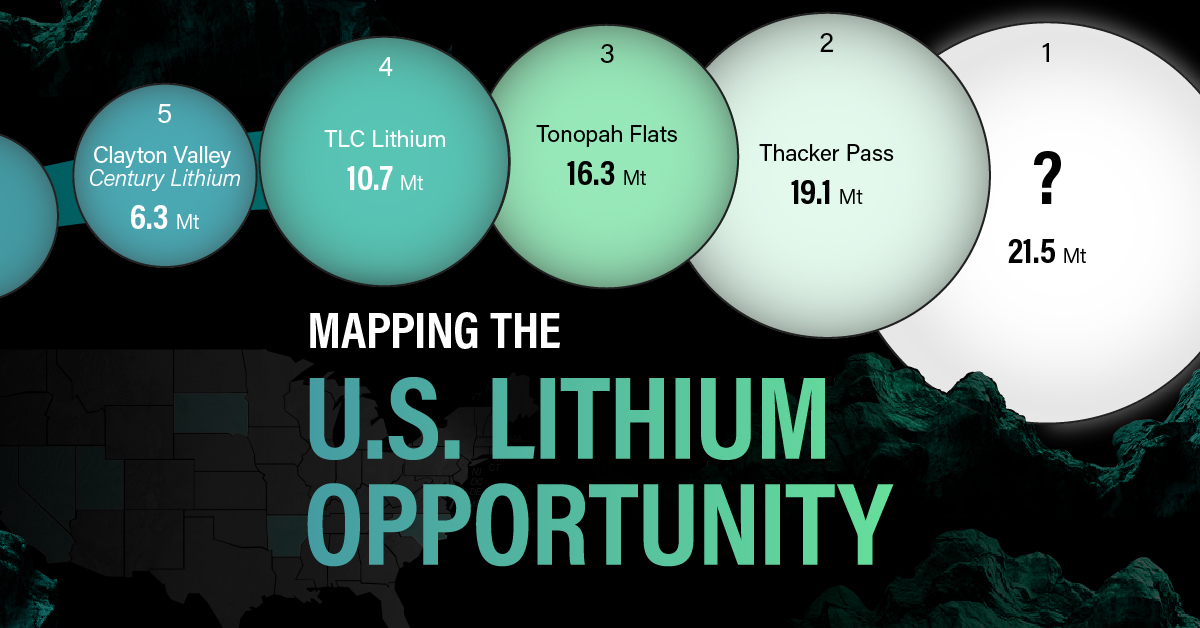

White Gold: Mapping U.S. Lithium Mines

In this graphic, Visual Capitalist partnerered with EnergyX to explore the size and location of U.S. lithium mines.

White Gold: Mapping U.S. Lithium Mines

The U.S. doubled imports of lithium-ion batteries for the third consecutive year in 2022, and with EV demand growing yearly, U.S. lithium mines must ramp up production or rely on other nations for their supply of refined lithium.

To determine if the domestic U.S. lithium opportunity can meet demand, we partnered with EnergyX to determine how much lithium sits within U.S. borders.

U.S. Lithium Projects

The most crucial measure of a lithium mine’s potential is the quantity that can be extracted from the source.

For each lithium resource, the potential volume of lithium carbonate equivalent (LCE) was calculated with a ratio of one metric ton of lithium producing 5.32 metric tons of LCE. Cumulatively, existing U.S. lithium projects contain 94.8 million metric tons of LCE.

| Rank | Project Name | LCE, million metric tons (est.) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | McDermitt Caldera | 21.5 |

| 2 | Thacker Pass | 19.1 |

| 3 | Tonopah Flats | 18.0 |

| 4 | TLC Lithium | 10.7 |

| 5 | Clayton Valley (Century Lithium) | 6.3 |

| 6 | Zeus Lithium | 6.3 |

| 7 | Rhyolite Ridge | 3.4 |

| 8 | Arkansas Smackover (Phase 1A) | 2.8 |

| 9 | Basin Project | 2.2 |

| 10 | McGee Deposit | 2.1 |

| 11 | Arkansas Smackover (South West) | 1.8 |

| 12 | Clayton Valley (Lithium-X, Pure Energy) | 0.8 |

| 13 | Big Sandy | 0.3 |

| 14 | Imperial Valley/Salton Sea | 0.3 |

U.S. Lithium Opportunities, By State

U.S. lithium projects mainly exist in western states, with comparatively minor opportunities in central or eastern states.

| State | LCE, million metric tons (est.) |

|---|---|

| Nevada | 88.2 |

| Arkansas | 4.6 |

| Arizona | 2.5 |

| California | 0.3 |

Currently, the U.S. is sitting on a wealth of lithium that it is underutilizing. For context, in 2022, the U.S. only produced about 5,000 metric tons of LCE and imported a projected 19,000 metric tons of LCE, showing that the demand for the mineral is healthy.

The Next Gold Rush?

U.S. lithium companies have the opportunity to become global leaders in lithium production and accelerate the transition to sustainable energy sources. This is particularly important as the demand for lithium is increasing every year.

EnergyX is on a mission to meet U.S. lithium demands using groundbreaking technology that can extract 300% more lithium from a source than traditional methods.

You can take advantage of this opportunity by investing in EnergyX and joining other significant players like GM in becoming a shareholder.

-

Electrification3 years ago

Electrification3 years agoRanked: The Top 10 EV Battery Manufacturers

-

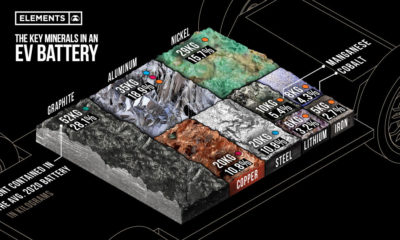

Electrification2 years ago

Electrification2 years agoThe Key Minerals in an EV Battery

-

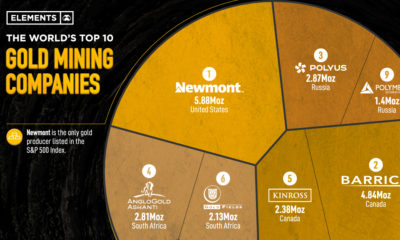

Real Assets3 years ago

Real Assets3 years agoThe World’s Top 10 Gold Mining Companies

-

Misc3 years ago

Misc3 years agoAll the Metals We Mined in One Visualization

-

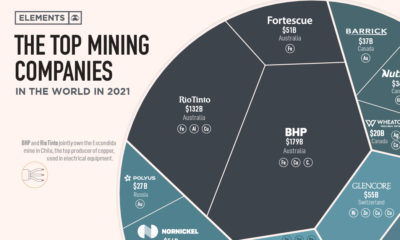

Electrification3 years ago

Electrification3 years agoThe Biggest Mining Companies in the World in 2021

-

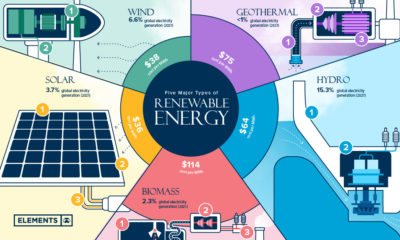

Energy Shift2 years ago

Energy Shift2 years agoWhat Are the Five Major Types of Renewable Energy?

-

Electrification2 years ago

Electrification2 years agoMapped: Solar Power by Country in 2021

-

Electrification2 years ago

Electrification2 years agoThe World’s Largest Nickel Mining Companies