Electrification

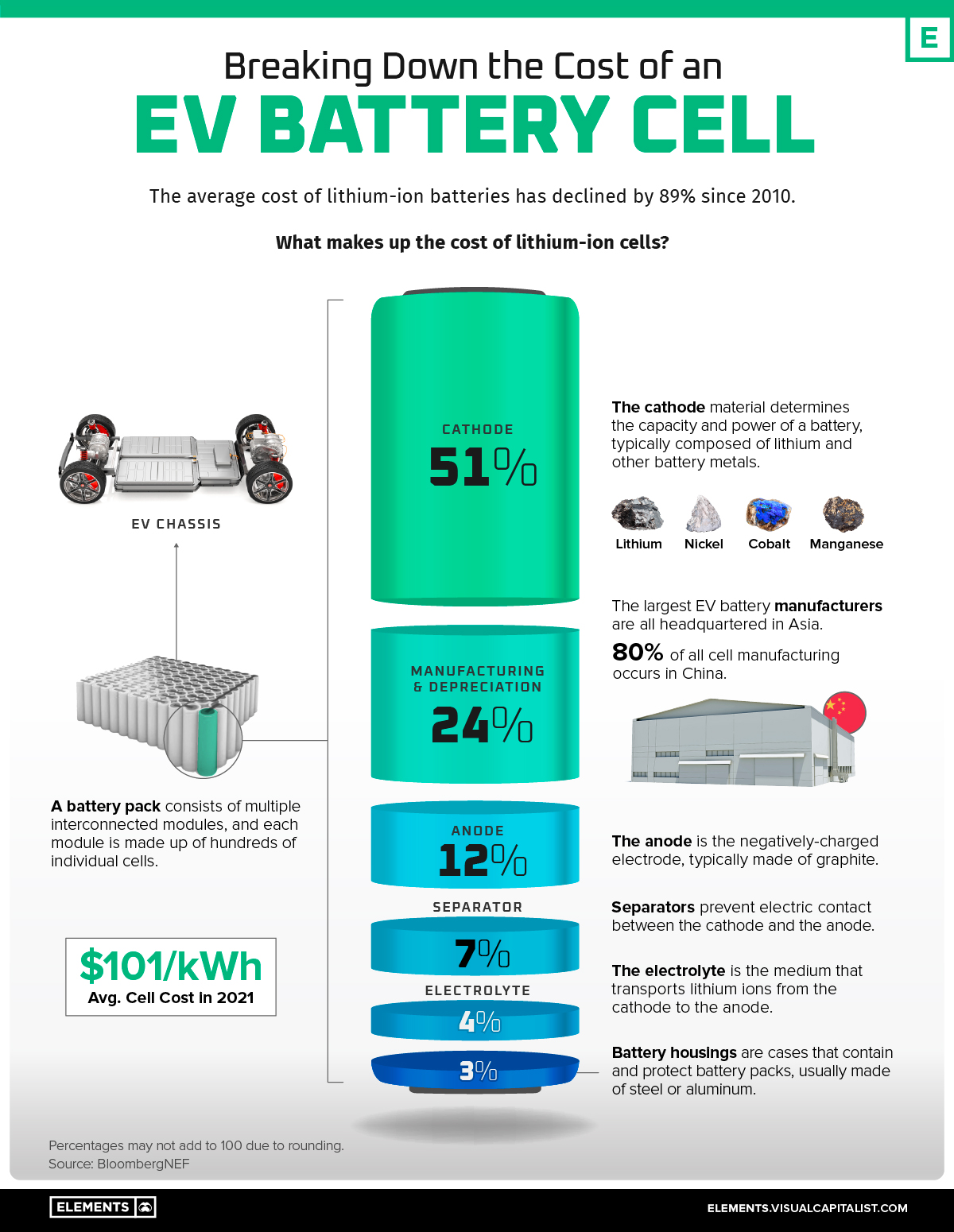

Breaking Down the Cost of an EV Battery Cell

Breaking Down the Cost of an EV Battery Cell

As electric vehicle (EV) battery prices keep dropping, the global supply of EVs and demand for their batteries are ramping up.

Since 2010, the average price of a lithium-ion (Li-ion) EV battery pack has fallen from $1,200 per kilowatt-hour (kWh) to just $132/kWh in 2021.

Inside each EV battery pack are multiple interconnected modules made up of tens to hundreds of rechargeable Li-ion cells. Collectively, these cells make up roughly 77% of the total cost of an average battery pack, or about $101/kWh.

So, what drives the cost of these individual battery cells?

The Cost of a Battery Cell

According to data from BloombergNEF, the cost of each cell’s cathode adds up to more than half of the overall cell cost.

| EV Battery Cell Component | % of Cell Cost |

|---|---|

| Cathode | 51% |

| Manufacturing and depreciation | 24% |

| Anode | 12% |

| Separator | 7% |

| Electrolyte | 4% |

| Housing and other materials | 3% |

Percentages may not add to 100% due to rounding.

Why Are Cathodes so Expensive?

The cathode is the positively charged electrode of the battery. When a battery is discharged, both electrons and positively-charged molecules (the eponymous lithium ions) flow from the anode to the cathode, which stores both until the battery is charged again.

That means that cathodes effectively determine the performance, range, and thermal safety of a battery, and therefore of an EV itself, making them one of the most important components.

They are composed of various metals (in refined forms) depending on cell chemistry, typically including lithium and nickel. Common cathode compositions in modern use include:

- Lithium iron phosphate (LFP)

- Lithium nickel manganese cobalt (NMC)

- Lithium nickel cobalt aluminum oxide (NCA)

The battery metals that make up the cathode are in high demand, with automakers like Tesla rushing to secure supplies as EV sales charge ahead. In fact, the commodities in the cathode, along with those in other parts of the cell, account for roughly 40% of the overall cell cost.

Other EV Battery Cell Components

Components outside of the cathode make up the other 49% of a cell’s cost.

The manufacturing process, which involves producing the electrodes, assembling the different components, and finishing the cell, makes up 24% of the total cost.

The anode is another significant component of the battery, and it makes up 12% of the total cost—around one-fourth of the cathode’s share. The anode in a Li-ion cell is typically made of natural or synthetic graphite, which tends to be less expensive than other battery commodities.

Although battery costs have been declining since 2010, the recent surge in prices of key battery metals like lithium has cast a shadow of doubt over their future. How will EV battery prices evolve going forward?

Electrification

Ranked: The Top 10 EV Battery Manufacturers in 2023

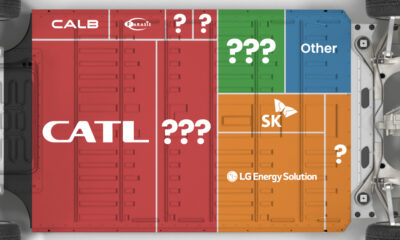

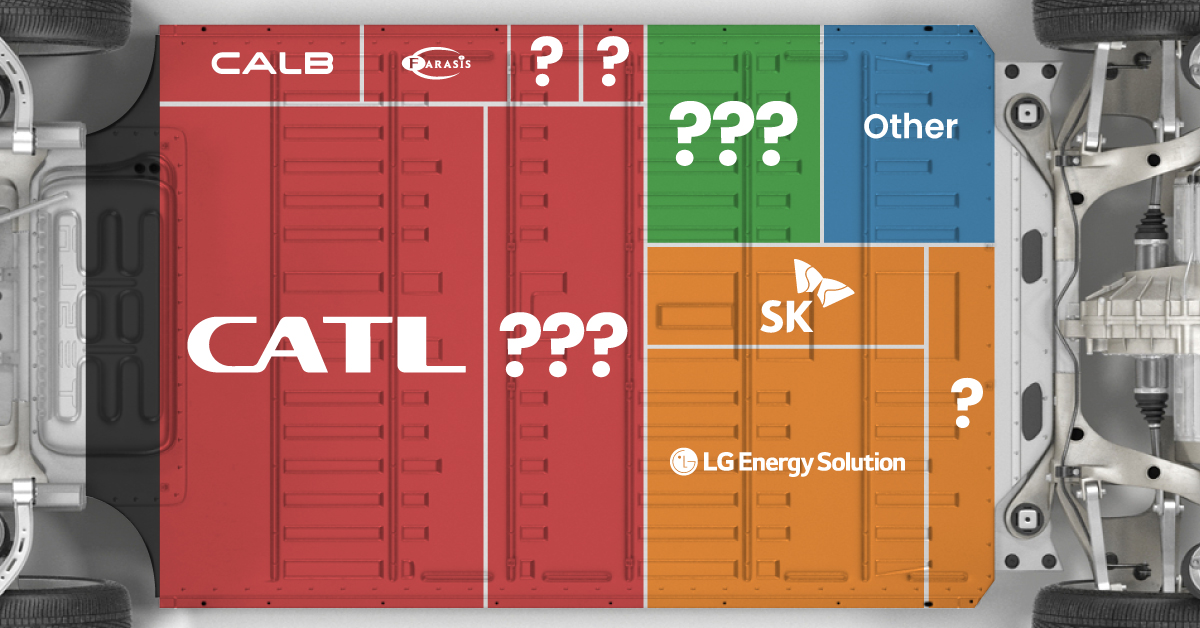

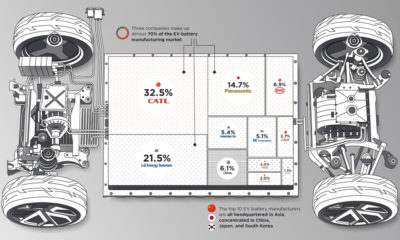

Asia dominates this ranking of the world’s largest EV battery manufacturers in 2023.

The Top 10 EV Battery Manufacturers in 2023

This was originally posted on our Voronoi app. Download the app for free on iOS or Android and discover incredible data-driven charts from a variety of trusted sources.

Despite efforts from the U.S. and EU to secure local domestic supply, all major EV battery manufacturers remain based in Asia.

In this graphic we rank the top 10 EV battery manufacturers by total battery deployment (measured in megawatt-hours) in 2023. The data is from EV Volumes.

Chinese Dominance

Contemporary Amperex Technology Co. Limited (CATL) has swiftly risen in less than a decade to claim the title of the largest global battery group.

The Chinese company now has a 34% share of the market and supplies batteries to a range of made-in-China vehicles, including the Tesla Model Y, SAIC’s MG4/Mulan, and Li Auto models.

| Company | Country | 2023 Production (megawatt-hour) | Share of Total Production |

|---|---|---|---|

| CATL | 🇨🇳China | 242,700 | 34% |

| BYD | 🇨🇳China | 115,917 | 16% |

| LG Energy Solution | 🇰🇷Korea | 108,487 | 15% |

| Panasonic | 🇯🇵Japan | 56,560 | 8% |

| SK On | 🇰🇷Korea | 40,711 | 6% |

| Samsung SDI | 🇰🇷Korea | 35,703 | 5% |

| CALB | 🇨🇳China | 23,493 | 3% |

| Farasis Energy | 🇨🇳China | 16,527 | 2% |

| Envision AESC | 🇨🇳China | 8,342 | 1% |

| Sunwoda | 🇨🇳China | 6,979 | 1% |

| Other | - | 56,040 | 8% |

In 2023, BYD surpassed LG Energy Solution to claim second place. This was driven by demand from its own models and growth in third-party deals, including providing batteries for the made-in-Germany Tesla Model Y, Toyota bZ3, Changan UNI-V, Venucia V-Online, as well as several Haval and FAW models.

The top three battery makers (CATL, BYD, LG) collectively account for two-thirds (66%) of total battery deployment.

Once a leader in the EV battery business, Panasonic now holds the fourth position with an 8% market share, down from 9% last year. With its main client, Tesla, now effectively sourcing batteries from multiple suppliers, the Japanese battery maker seems to be losing its competitive edge in the industry.

Overall, the global EV battery market size is projected to grow from $49 billion in 2022 to $98 billion by 2029, according to Fortune Business Insights.

Electrification

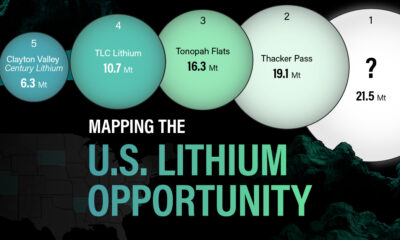

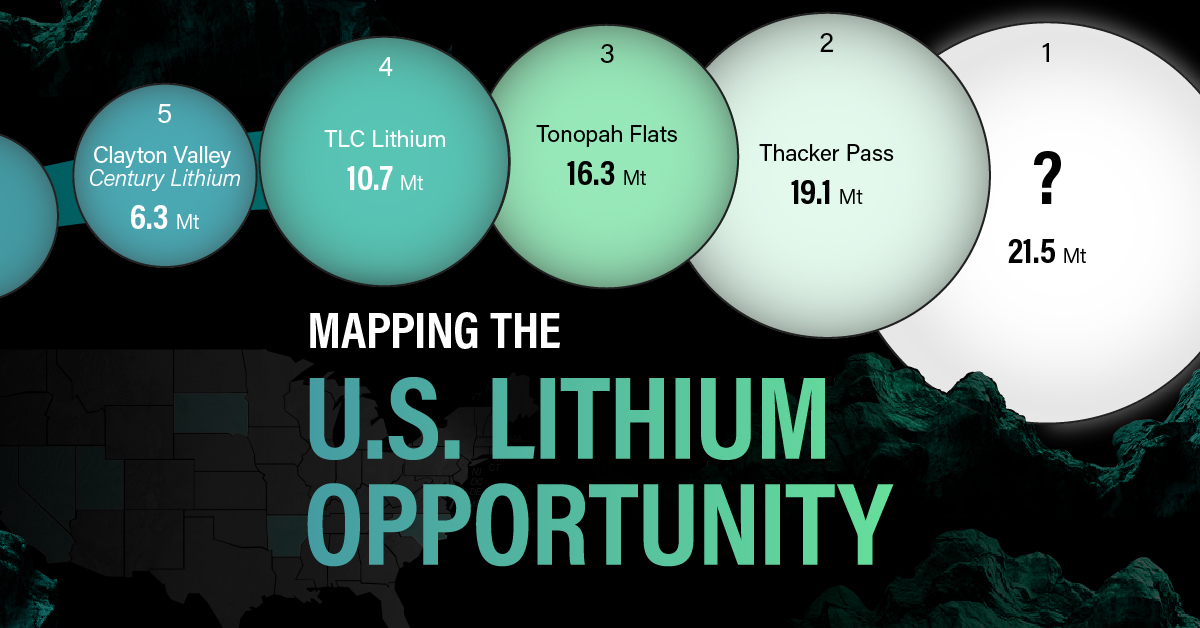

White Gold: Mapping U.S. Lithium Mines

In this graphic, Visual Capitalist partnerered with EnergyX to explore the size and location of U.S. lithium mines.

White Gold: Mapping U.S. Lithium Mines

The U.S. doubled imports of lithium-ion batteries for the third consecutive year in 2022, and with EV demand growing yearly, U.S. lithium mines must ramp up production or rely on other nations for their supply of refined lithium.

To determine if the domestic U.S. lithium opportunity can meet demand, we partnered with EnergyX to determine how much lithium sits within U.S. borders.

U.S. Lithium Projects

The most crucial measure of a lithium mine’s potential is the quantity that can be extracted from the source.

For each lithium resource, the potential volume of lithium carbonate equivalent (LCE) was calculated with a ratio of one metric ton of lithium producing 5.32 metric tons of LCE. Cumulatively, existing U.S. lithium projects contain 94.8 million metric tons of LCE.

| Rank | Project Name | LCE, million metric tons (est.) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | McDermitt Caldera | 21.5 |

| 2 | Thacker Pass | 19.1 |

| 3 | Tonopah Flats | 18.0 |

| 4 | TLC Lithium | 10.7 |

| 5 | Clayton Valley (Century Lithium) | 6.3 |

| 6 | Zeus Lithium | 6.3 |

| 7 | Rhyolite Ridge | 3.4 |

| 8 | Arkansas Smackover (Phase 1A) | 2.8 |

| 9 | Basin Project | 2.2 |

| 10 | McGee Deposit | 2.1 |

| 11 | Arkansas Smackover (South West) | 1.8 |

| 12 | Clayton Valley (Lithium-X, Pure Energy) | 0.8 |

| 13 | Big Sandy | 0.3 |

| 14 | Imperial Valley/Salton Sea | 0.3 |

U.S. Lithium Opportunities, By State

U.S. lithium projects mainly exist in western states, with comparatively minor opportunities in central or eastern states.

| State | LCE, million metric tons (est.) |

|---|---|

| Nevada | 88.2 |

| Arkansas | 4.6 |

| Arizona | 2.5 |

| California | 0.3 |

Currently, the U.S. is sitting on a wealth of lithium that it is underutilizing. For context, in 2022, the U.S. only produced about 5,000 metric tons of LCE and imported a projected 19,000 metric tons of LCE, showing that the demand for the mineral is healthy.

The Next Gold Rush?

U.S. lithium companies have the opportunity to become global leaders in lithium production and accelerate the transition to sustainable energy sources. This is particularly important as the demand for lithium is increasing every year.

EnergyX is on a mission to meet U.S. lithium demands using groundbreaking technology that can extract 300% more lithium from a source than traditional methods.

You can take advantage of this opportunity by investing in EnergyX and joining other significant players like GM in becoming a shareholder.

-

Electrification3 years ago

Electrification3 years agoRanked: The Top 10 EV Battery Manufacturers

-

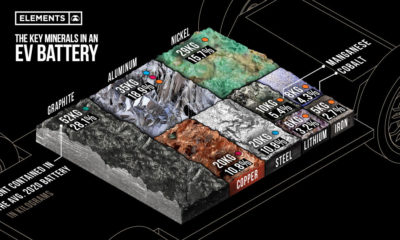

Electrification2 years ago

Electrification2 years agoThe Key Minerals in an EV Battery

-

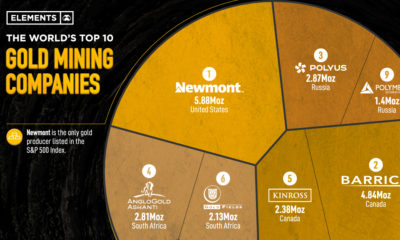

Real Assets3 years ago

Real Assets3 years agoThe World’s Top 10 Gold Mining Companies

-

Misc3 years ago

Misc3 years agoAll the Metals We Mined in One Visualization

-

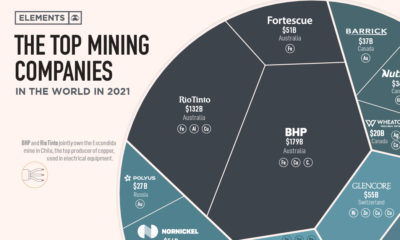

Electrification3 years ago

Electrification3 years agoThe Biggest Mining Companies in the World in 2021

-

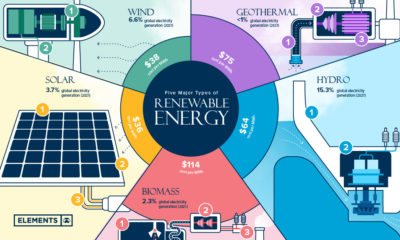

Energy Shift2 years ago

Energy Shift2 years agoWhat Are the Five Major Types of Renewable Energy?

-

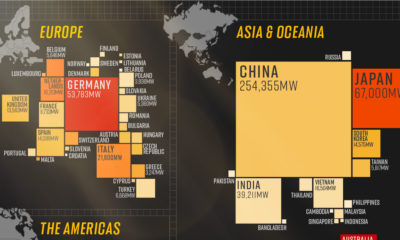

Electrification2 years ago

Electrification2 years agoMapped: Solar Power by Country in 2021

-

Electrification2 years ago

Electrification2 years agoThe World’s Largest Nickel Mining Companies