Electrification

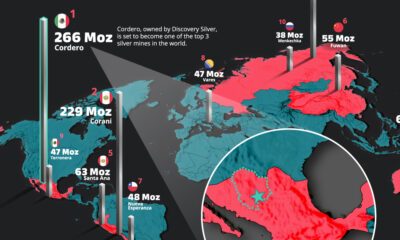

Visualized: The Silver Mining Journey From Ore to More

The following content is sponsored by Silver X.

The Silver Mining Journey From Ore to More

Silver has been a monetary metal and used in jewelry for thousands of years, but today, silver is powering the green energy transition and new tech innovation. With the greatest electrical conductivity of all metals, silver is used in electrical contacts and circuit boards, along with solar panels, electric vehicles, and 5G devices.

Behind the large collection of silver-dependent products and technologies is an active mining industry that must supply the necessary metal. So how exactly is the silver mined and produced?

This graphic from our sponsor Silver X walks us through how we mine and refine silver along with the growing demand for the metal which will fuel the economy of the future.

Getting Silver Out of the Ground

Like many other metals, silver is found in the Earth’s crust and primarily mined using heavy machinery and explosives.

Once a silver bearing ore body has been identified and can be mined at a reasonable cost, the mining method is chosen depending on the nature of the ore body along with other factors like location and infrastructure:

- Open pit mining: Best for mining large amounts of lower grade silver ore near the surface

- Underground shaft mining: Best for following and mining high-grade veins of silver ore further underground

While in open pit mining a huge volume of land is displaced across a large surface area, it is typically safer overall compared to underground mines.

Despite their differences, both methods ultimately use explosives to break up chunks of ore into easily transportable pieces that are then brought to crushing facilities for the next step.

Crushing and Separating Mined Silver Ore

Once the ore has been mined and transported out of the mine, it goes through a variety of crushers which break down the ore into small chunks. The chunks of silver ore are crushed and ground into a fine powder, allowing for the separation process to begin.

There are two primary methods of silver separation, and both involve mixing the silver ore powder with water to form a slurry.

In the flotation process of separation, chemicals are added to the slurry to make any silver and lead water repellent. Air bubbles are then blown through the slurry, with the silver and lead sticking to the bubbles and rising to the top of the slurry where they are separated and dried out.

In the tank leaching and Merill-Crowe process, cyanide is added to the slurry to ensure the silver dissolves into the solution. Then, solids are filtered out in a settling tank, with the silver solution deaerated before zinc powder is added. The solution then passes through a set of filter plates and presses which collect the zinc and silver precipitate which is dried off.

Processing and Refining to Pure Silver

Once the silver ore has been largely broken down and separated from much of the waste rock, the silver must be completely extracted from the remaining metals. Typically, two different processes are used depending on the other metal that must be separated from.

- Electrolytic Refining (Copper): This method places the copper-silver concentrate in an electrolytic cell within an electrolyte solution. Electricity is passed through the solution, resulting in the copper and silver separating out to opposite ends of the cell. The process is repeated until only silver remains, which is then collected and smelted to remove any remaining impurities.

- Parkes Process (Lead): This method adds zinc to the molten lead-silver solution, since silver is attracted to zinc while lead is repelled. The silver and zinc compound floats to the top and is skimmed off before being heated and distilled until only pure silver remains.

Silver’s Growing Industry and Investment Demand

In 2020, 784.4 million ounces of silver were mined across the world according to Metals Focus. While production is forecasted to increase by ~8% to reach 848.5 million ounces in 2021, it’s still greatly outpaced by growing demand for silver.

Silver demand is forecasted to see a 15% YoY increase from 2020’s 896.1 million ounces to 1,033 million ounces forecasted for 2021. Solar panels have been one of the largest industrial drivers for silver demand, with demand more than doubling since 2014, from 48.4 million ounces to 105 million ounces forecasted for 2021.

| Year | Silver Production (in million ounces) | YoY % Change | Total Silver Demand (in million ounces) | YoY % Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 862.9 | -4.1% | 966.0 | -3.1% |

| 2018 | 848.4 | -1.7% | 989.8 | 2.5% |

| 2019 | 833.2 | -1.8% | 995.4 | 0.6% |

| 2020 | 784.4 | -5.9% | 896.1 | -9.9% |

| 2021F | 848.5 | 8.2% | 1,033.0 | 15.3% |

Investment has also been a key demand driver for silver, especially since Reddit’s WallStreetBets crowd began pursuing the possibility of a silver short squeeze. Net physical investment demand rose 29.4% from 2017’s 156.2 million ounces to 200.5 million ounces in 2020, and 2021 is forecasted to see a 26.1% increase with a net investment demand of 252.8 million ounces.

Whether driven by investors or industries, silver is in high demand as the world shifts to newer and greener technologies. The process of silver mining, extraction, and refining will continue to play a pivotal role in supplying the world with the silver it needs.

Electrification

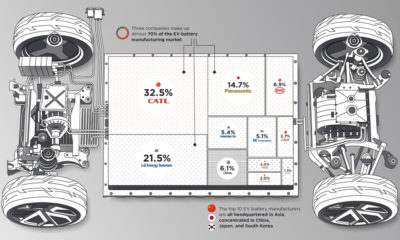

Ranked: The Top 10 EV Battery Manufacturers in 2023

Asia dominates this ranking of the world’s largest EV battery manufacturers in 2023.

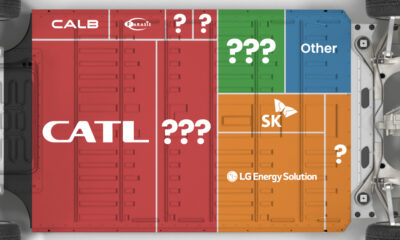

The Top 10 EV Battery Manufacturers in 2023

This was originally posted on our Voronoi app. Download the app for free on iOS or Android and discover incredible data-driven charts from a variety of trusted sources.

Despite efforts from the U.S. and EU to secure local domestic supply, all major EV battery manufacturers remain based in Asia.

In this graphic we rank the top 10 EV battery manufacturers by total battery deployment (measured in megawatt-hours) in 2023. The data is from EV Volumes.

Chinese Dominance

Contemporary Amperex Technology Co. Limited (CATL) has swiftly risen in less than a decade to claim the title of the largest global battery group.

The Chinese company now has a 34% share of the market and supplies batteries to a range of made-in-China vehicles, including the Tesla Model Y, SAIC’s MG4/Mulan, and Li Auto models.

| Company | Country | 2023 Production (megawatt-hour) | Share of Total Production |

|---|---|---|---|

| CATL | 🇨🇳China | 242,700 | 34% |

| BYD | 🇨🇳China | 115,917 | 16% |

| LG Energy Solution | 🇰🇷Korea | 108,487 | 15% |

| Panasonic | 🇯🇵Japan | 56,560 | 8% |

| SK On | 🇰🇷Korea | 40,711 | 6% |

| Samsung SDI | 🇰🇷Korea | 35,703 | 5% |

| CALB | 🇨🇳China | 23,493 | 3% |

| Farasis Energy | 🇨🇳China | 16,527 | 2% |

| Envision AESC | 🇨🇳China | 8,342 | 1% |

| Sunwoda | 🇨🇳China | 6,979 | 1% |

| Other | - | 56,040 | 8% |

In 2023, BYD surpassed LG Energy Solution to claim second place. This was driven by demand from its own models and growth in third-party deals, including providing batteries for the made-in-Germany Tesla Model Y, Toyota bZ3, Changan UNI-V, Venucia V-Online, as well as several Haval and FAW models.

The top three battery makers (CATL, BYD, LG) collectively account for two-thirds (66%) of total battery deployment.

Once a leader in the EV battery business, Panasonic now holds the fourth position with an 8% market share, down from 9% last year. With its main client, Tesla, now effectively sourcing batteries from multiple suppliers, the Japanese battery maker seems to be losing its competitive edge in the industry.

Overall, the global EV battery market size is projected to grow from $49 billion in 2022 to $98 billion by 2029, according to Fortune Business Insights.

Electrification

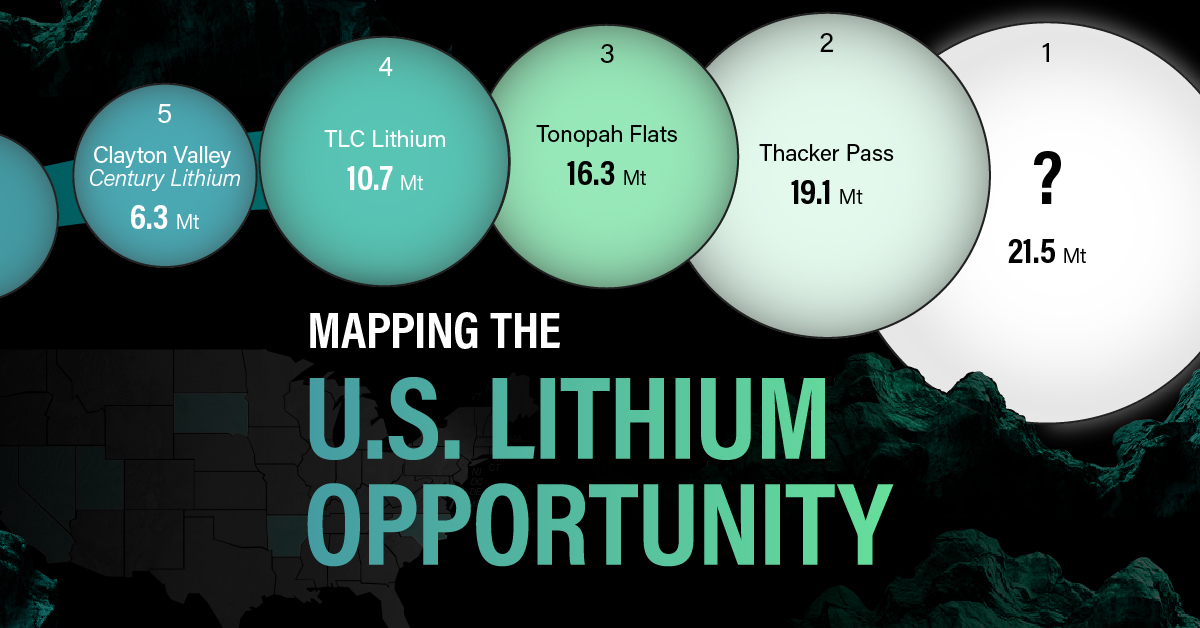

White Gold: Mapping U.S. Lithium Mines

In this graphic, Visual Capitalist partnerered with EnergyX to explore the size and location of U.S. lithium mines.

White Gold: Mapping U.S. Lithium Mines

The U.S. doubled imports of lithium-ion batteries for the third consecutive year in 2022, and with EV demand growing yearly, U.S. lithium mines must ramp up production or rely on other nations for their supply of refined lithium.

To determine if the domestic U.S. lithium opportunity can meet demand, we partnered with EnergyX to determine how much lithium sits within U.S. borders.

U.S. Lithium Projects

The most crucial measure of a lithium mine’s potential is the quantity that can be extracted from the source.

For each lithium resource, the potential volume of lithium carbonate equivalent (LCE) was calculated with a ratio of one metric ton of lithium producing 5.32 metric tons of LCE. Cumulatively, existing U.S. lithium projects contain 94.8 million metric tons of LCE.

| Rank | Project Name | LCE, million metric tons (est.) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | McDermitt Caldera | 21.5 |

| 2 | Thacker Pass | 19.1 |

| 3 | Tonopah Flats | 18.0 |

| 4 | TLC Lithium | 10.7 |

| 5 | Clayton Valley (Century Lithium) | 6.3 |

| 6 | Zeus Lithium | 6.3 |

| 7 | Rhyolite Ridge | 3.4 |

| 8 | Arkansas Smackover (Phase 1A) | 2.8 |

| 9 | Basin Project | 2.2 |

| 10 | McGee Deposit | 2.1 |

| 11 | Arkansas Smackover (South West) | 1.8 |

| 12 | Clayton Valley (Lithium-X, Pure Energy) | 0.8 |

| 13 | Big Sandy | 0.3 |

| 14 | Imperial Valley/Salton Sea | 0.3 |

U.S. Lithium Opportunities, By State

U.S. lithium projects mainly exist in western states, with comparatively minor opportunities in central or eastern states.

| State | LCE, million metric tons (est.) |

|---|---|

| Nevada | 88.2 |

| Arkansas | 4.6 |

| Arizona | 2.5 |

| California | 0.3 |

Currently, the U.S. is sitting on a wealth of lithium that it is underutilizing. For context, in 2022, the U.S. only produced about 5,000 metric tons of LCE and imported a projected 19,000 metric tons of LCE, showing that the demand for the mineral is healthy.

The Next Gold Rush?

U.S. lithium companies have the opportunity to become global leaders in lithium production and accelerate the transition to sustainable energy sources. This is particularly important as the demand for lithium is increasing every year.

EnergyX is on a mission to meet U.S. lithium demands using groundbreaking technology that can extract 300% more lithium from a source than traditional methods.

You can take advantage of this opportunity by investing in EnergyX and joining other significant players like GM in becoming a shareholder.

-

Electrification3 years ago

Electrification3 years agoRanked: The Top 10 EV Battery Manufacturers

-

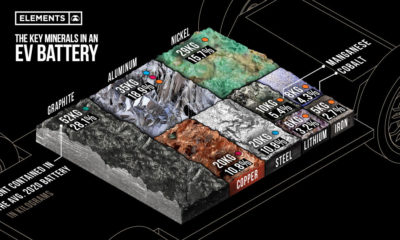

Electrification2 years ago

Electrification2 years agoThe Key Minerals in an EV Battery

-

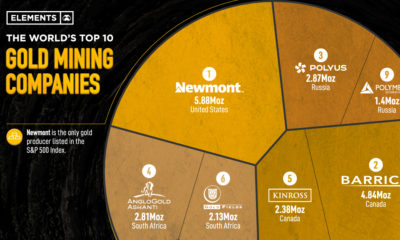

Real Assets3 years ago

Real Assets3 years agoThe World’s Top 10 Gold Mining Companies

-

Misc3 years ago

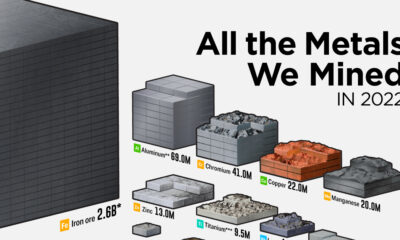

Misc3 years agoAll the Metals We Mined in One Visualization

-

Electrification3 years ago

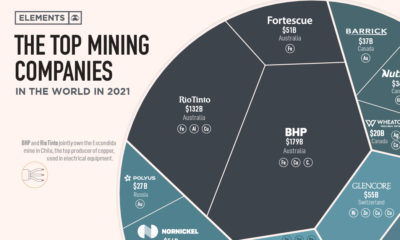

Electrification3 years agoThe Biggest Mining Companies in the World in 2021

-

Energy Shift2 years ago

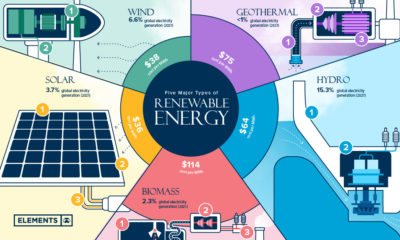

Energy Shift2 years agoWhat Are the Five Major Types of Renewable Energy?

-

Electrification2 years ago

Electrification2 years agoThe World’s Largest Nickel Mining Companies

-

Electrification2 years ago

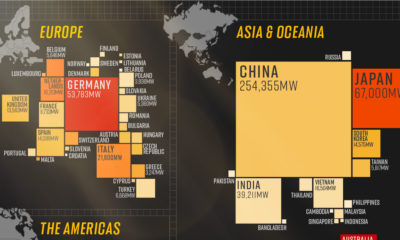

Electrification2 years agoMapped: Solar Power by Country in 2021