Electrification

Every Electric Semi Truck in One Graphic

Every Electric Semi Truck in One Graphic

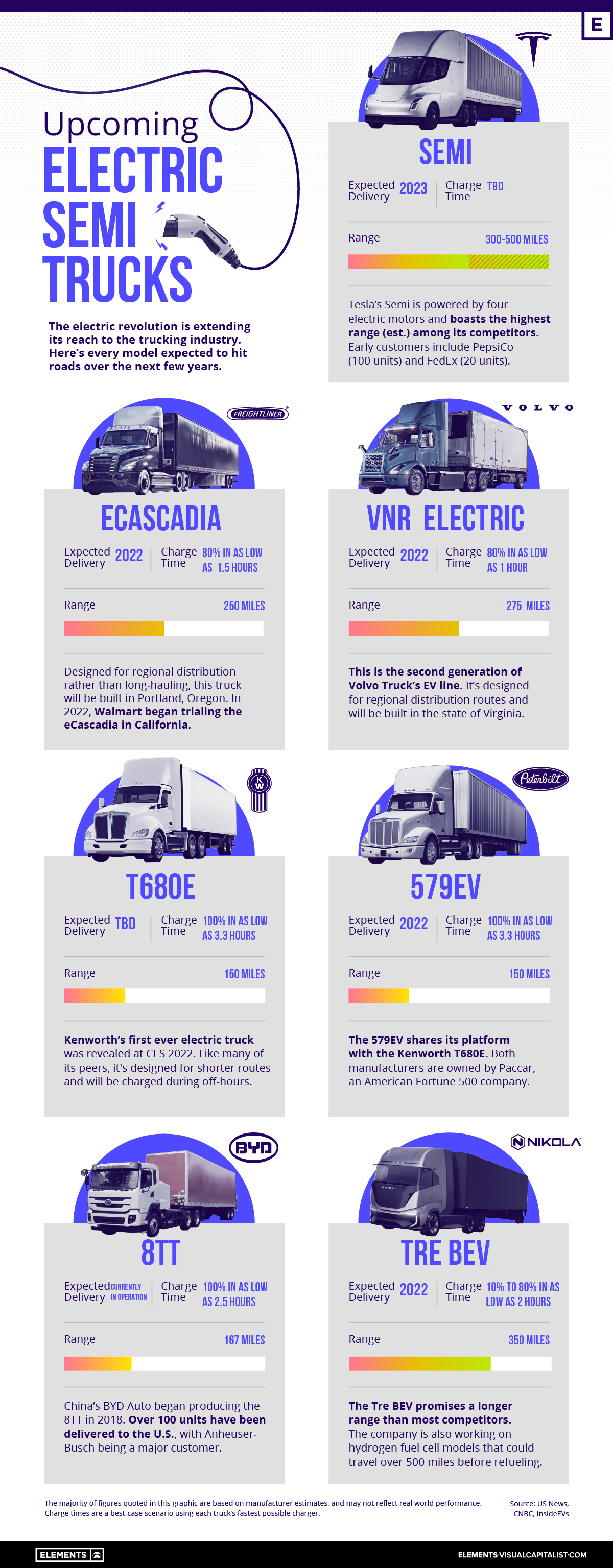

Electric semi trucks are coming, and they could help to decarbonize the shipping and logistics industry. However, range remains a major limitation.

This presents challenges for long-hauling, where the average diesel-powered semi can travel up to 2,000 miles before refueling. Compare this to the longest range electric model, the Tesla Semi, which promises up to 500 miles. A key word here is “promises”—the Semi is still in development, and nothing has been proven yet.

In this infographic, we’ve listed all of the upcoming electric semi trucks, complete with range and charge time estimates. Further in the article, we’ll explore the potential commercial use cases of this first generation of trucks.

Model Overview

The following table includes all of the models included in the above infographic.

| Company | Truck Name | Range | Charge Time | Expected Delivery |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 🇺🇸 Tesla | Semi | 300-500 miles | TBD | 2023 |

| 🇺🇸 Freightliner | eCascadia | 250 miles | 80% in as low as 1.5 hrs | 2022 |

| 🇸🇪 Volvo | VNR Electric | 275 miles | 80% in as low as 1 hr | 2022 |

| 🇺🇸 Kenworth | T680E | 150 miles | 100% in as low as 3.3 hrs | TBD |

| 🇺🇸 Peterbilt | 579EV | 150 miles | 100% in as low as 3.3 hrs | 2022 |

| 🇨🇳 BYD | 8TT | 167 miles | 100% in as low as 2.5 hrs | In operation |

| 🇺🇸 Nikola | Tre BEV | 350 miles | 10% to 80% in as low as 2 hrs | 2022 |

Source: US News, CNBC, InsideEVs

With the exception of Tesla’s Semi, all of these trucks are currently in operation or expected to begin delivering this year. You may want to take this with a grain of salt, as the electric vehicle industry has become notorious for delays.

In terms of range, Tesla and Nikola are promising the highest figures (300+ miles), while the rest of the competition is targeting between 150 to 275 miles. It’s reasonable to assume that the Tesla and Nikola semis will be the most expensive.

Charge times are difficult to compare because of the variables involved. This includes the amount of charge and the type of charger used. Nikola, for example, claims it will take 2 hours to charge its Tre BEV from 10% to 80% when using a 240kW charger.

Charger technology is also improving quickly. Tesla is believed to be rolling out a 1 MW (1,000 kW) charger that could add 400 miles of range in just 30 minutes.

Use Cases of Electric Semi Trucks

Given their relatively lower ranges, electric semis are unlikely to be used for long hauls.

Instead, they’re expected to be deployed on regional and urban routes, where the total distance traveled between destinations is much lower. There are many reasons why electric semis are suited for these routes, as listed below:

- Smaller batteries can be installed, which keeps the cost of the truck lower

- Urban routes provide greater opportunities to use regenerative braking

- Quieter and cleaner operation in densely populated areas

An example of a regional route would be delivering containers from the Port of Los Angeles to the Los Angeles Transportation Center Intermodal Facility (LATC). The LATC is where containers are loaded onto trains, and is located roughly 28 miles away.

With a round trip totaling nearly 60 miles, an electric semi with a range of 200 miles could feasibly complete this route three times before needing a charge. The truck could be charged overnight, as well as during off hours in the middle of the day.

Hydrogen for Long Hauls?

We’ve covered the differences between battery and hydrogen fuel cell vehicles in the past, but this was from a passenger car perspective. The conclusion, in that case, was that battery electric has become the dominant technology. In terms of long-haul trucking, however, hydrogen may have an edge.

If we look at what will become mainstream, probably for smaller mobility it will be EVs, and fuel cells for larger mobility. That is the conclusion so far.

-Toshihiro Mibe, CEO, Honda

There are several reasons for why hydrogen could be beneficial for delivering heavy cargo over long distances. These are listed below:

- Refueling a hydrogen fuel cell takes less time than recharging a battery. Note, however, that charge times are still improving.

- A fuel cell configuration is typically lighter than an equivalent battery pack. Less drivetrain weight translates to a higher cargo capacity.

- Hydrogen-powered trucks could achieve a much higher range.

This last point hasn’t been proven yet, but we can reference Nikola, which is developing hydrogen-powered semi trucks. The company has two models in the works, which are the Tre FCEV with a range of 500 miles, and the Two FCEV with a range of 900 miles.

Keep in mind that these numbers are once again estimates and that Nikola has been accused of fraud in the past.

Who’s Using Electric Semi Trucks Today?

Although there are very few models available, electric semi trucks are indeed being used today.

In January 2020, Anheuser-Busch announced that it had received its 100th 8TT. The 8TT is produced by China’s BYD Motors and was one of the first electric semis to see real-world application. The brewing company uses its 8TTs to deliver products to retail destinations across California (e.g. grocery stores).

Another U.S. company using electric semis is Walmart. The retailer is trialing both the eCascadia from Freightliner and the Tre BEV from Nikola. The trucks are being used to pick up cargo from suppliers and then deliver it to regional consolidation centers.

Electrification

White Gold: Mapping U.S. Lithium Mines

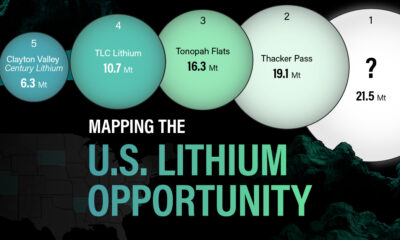

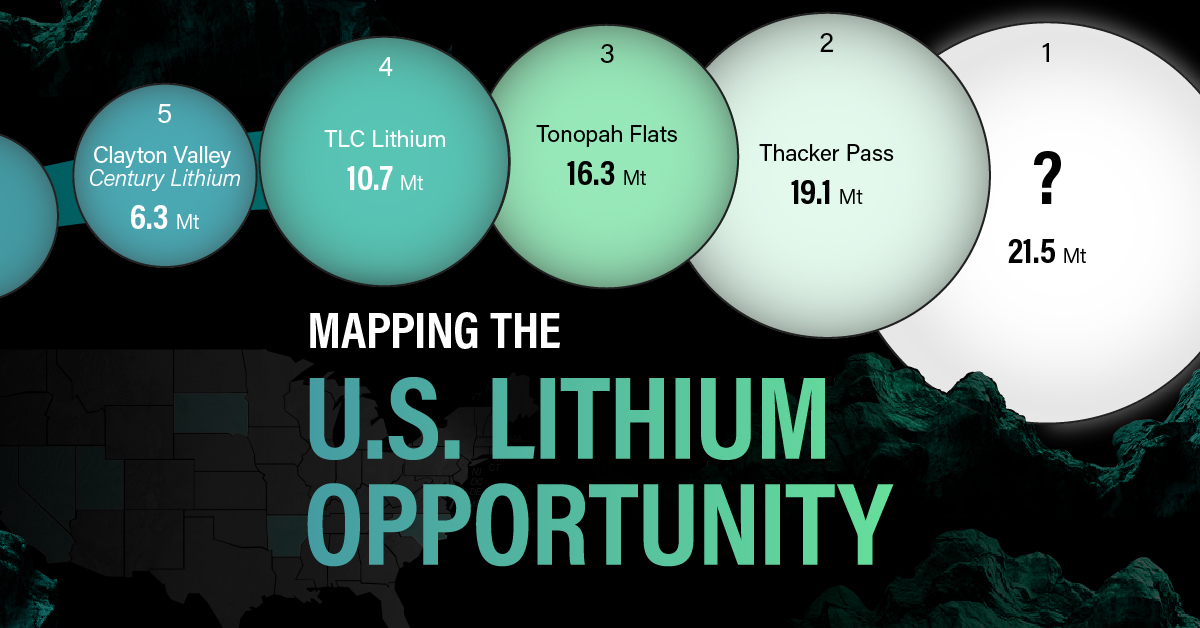

In this graphic, Visual Capitalist partnerered with EnergyX to explore the size and location of U.S. lithium mines.

White Gold: Mapping U.S. Lithium Mines

The U.S. doubled imports of lithium-ion batteries for the third consecutive year in 2022, and with EV demand growing yearly, U.S. lithium mines must ramp up production or rely on other nations for their supply of refined lithium.

To determine if the domestic U.S. lithium opportunity can meet demand, we partnered with EnergyX to determine how much lithium sits within U.S. borders.

U.S. Lithium Projects

The most crucial measure of a lithium mine’s potential is the quantity that can be extracted from the source.

For each lithium resource, the potential volume of lithium carbonate equivalent (LCE) was calculated with a ratio of one metric ton of lithium producing 5.32 metric tons of LCE. Cumulatively, existing U.S. lithium projects contain 94.8 million metric tons of LCE.

| Rank | Project Name | LCE, million metric tons (est.) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | McDermitt Caldera | 21.5 |

| 2 | Thacker Pass | 19.1 |

| 3 | Tonopah Flats | 18.0 |

| 4 | TLC Lithium | 10.7 |

| 5 | Clayton Valley (Century Lithium) | 6.3 |

| 6 | Zeus Lithium | 6.3 |

| 7 | Rhyolite Ridge | 3.4 |

| 8 | Arkansas Smackover (Phase 1A) | 2.8 |

| 9 | Basin Project | 2.2 |

| 10 | McGee Deposit | 2.1 |

| 11 | Arkansas Smackover (South West) | 1.8 |

| 12 | Clayton Valley (Lithium-X, Pure Energy) | 0.8 |

| 13 | Big Sandy | 0.3 |

| 14 | Imperial Valley/Salton Sea | 0.3 |

U.S. Lithium Opportunities, By State

U.S. lithium projects mainly exist in western states, with comparatively minor opportunities in central or eastern states.

| State | LCE, million metric tons (est.) |

|---|---|

| Nevada | 88.2 |

| Arkansas | 4.6 |

| Arizona | 2.5 |

| California | 0.3 |

Currently, the U.S. is sitting on a wealth of lithium that it is underutilizing. For context, in 2022, the U.S. only produced about 5,000 metric tons of LCE and imported a projected 19,000 metric tons of LCE, showing that the demand for the mineral is healthy.

The Next Gold Rush?

U.S. lithium companies have the opportunity to become global leaders in lithium production and accelerate the transition to sustainable energy sources. This is particularly important as the demand for lithium is increasing every year.

EnergyX is on a mission to meet U.S. lithium demands using groundbreaking technology that can extract 300% more lithium from a source than traditional methods.

You can take advantage of this opportunity by investing in EnergyX and joining other significant players like GM in becoming a shareholder.

Electrification

Will Direct Lithium Extraction Disrupt the $90B Lithium Market?

Visual Capitalist and EnergyX explore how direct lithium extraction could disrupt the $90B lithium industry.

Will Direct Lithium Extraction Disrupt the $90B Lithium Market?

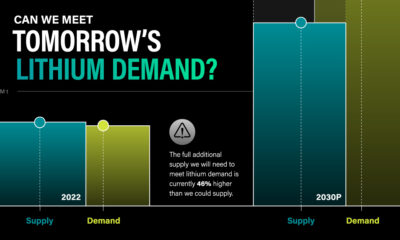

Current lithium extraction and refinement methods are outdated, often harmful to the environment, and ultimately inefficient. So much so that by 2030, lithium demand will outstrip supply by a projected 1.42 million metric tons. But there is a solution: Direct lithium extraction (DLE).

For this graphic, we partnered with EnergyX to try to understand how DLE could help meet global lithium demands and change an industry that is critical to the clean energy transition.

The Lithium Problem

Lithium is crucial to many renewable energy technologies because it is this element that allows EV batteries to react. In fact, it’s so important that projections show the lithium industry growing from $22.2B in 2023 to nearly $90B by 2030.

But even with this incredible growth, as you can see from the table, refined lithium production will need to increase 86.5% over and above current projections.

| 2022 (million metric tons) | 2030P (million metric tons) | |

|---|---|---|

| Lithium Carbonate Demand | 0.46 | 1.21 |

| Lithium Hydroxide Demand | 0.18 | 1.54 |

| Lithium Metal Demand | 0 | 0.22 |

| Lithium Mineral Demand | 0.07 | 0.09 |

| Total Demand | 0.71 | 3.06 |

| Total Supply | 0.75 | 1.64 |

The Solution: Direct Lithium Extraction

DLE is a process that uses a combination of solvent extraction, membranes, or adsorbents to extract and then refine lithium directly from its source. LiTASTM, the proprietary DLE technology developed by EnergyX, can recover an incredible 300% more lithium per ton than existing processes, making it the perfect tool to help meet lithium demands.

Additionally, LiTASTM can refine lithium at the lowest cost per unit volume directly from brine, an essential step in meeting tomorrow’s lithium demand and manufacturing next-generation batteries, while significantly reducing the footprint left by lithium mining.

| Hard Rock Mining | Underground Reservoirs | Direct Lithium Extraction | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct CO2 Emissions | 15,000 kg | 5,000 kg | 3.5 kg |

| Water Use | 170 m3 | 469 m3 | 34-94 m3 |

| Lithium Recovery Rate | 58% | 30-40% | 90% |

| Land Use | 464 m2 | 3124 m2 | 0.14 m2 |

| Process Time | Variable | 18 months | 1-2 days |

Providing the World with Lithium

DLE promises to disrupt the outdated lithium industry by improving lithium recovery rates and slashing emissions, helping the world meet the energy demands of tomorrow’s electric vehicles.

EnergyX is on a mission to become a worldwide leader in the sustainable energy transition using groundbreaking direct lithium extraction technology. Don’t miss your chance to join companies like GM and invest in EnergyX to transform the future of renewable energy.

-

Electrification3 years ago

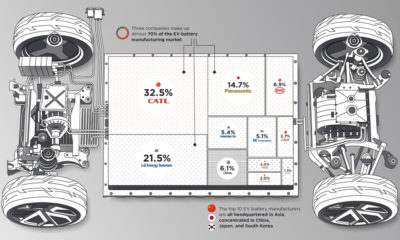

Electrification3 years agoRanked: The Top 10 EV Battery Manufacturers

-

Electrification2 years ago

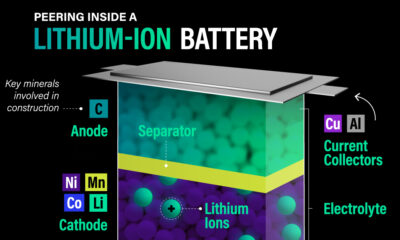

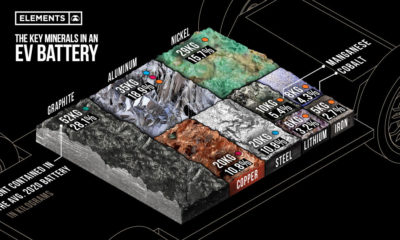

Electrification2 years agoThe Key Minerals in an EV Battery

-

Real Assets3 years ago

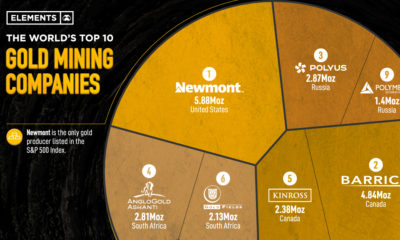

Real Assets3 years agoThe World’s Top 10 Gold Mining Companies

-

Misc3 years ago

Misc3 years agoAll the Metals We Mined in One Visualization

-

Electrification3 years ago

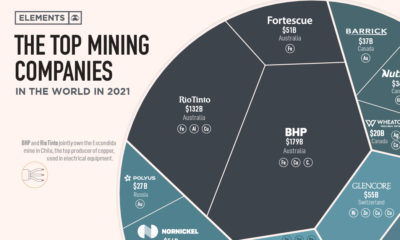

Electrification3 years agoThe Biggest Mining Companies in the World in 2021

-

Energy Shift2 years ago

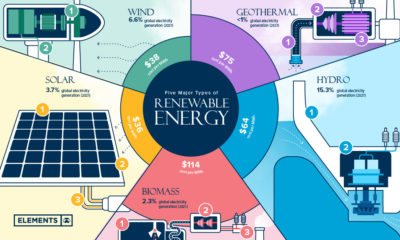

Energy Shift2 years agoWhat Are the Five Major Types of Renewable Energy?

-

Electrification2 years ago

Electrification2 years agoThe World’s Largest Nickel Mining Companies

-

Electrification2 years ago

Electrification2 years agoMapped: Solar Power by Country in 2021